HIDING THE GUNS FROM OUR MOUTHS: THE STREET MILK OF DARKNESS

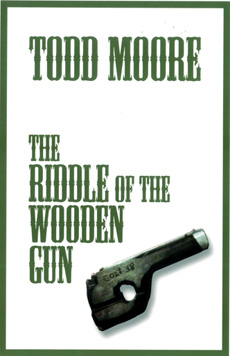

by Todd Moore

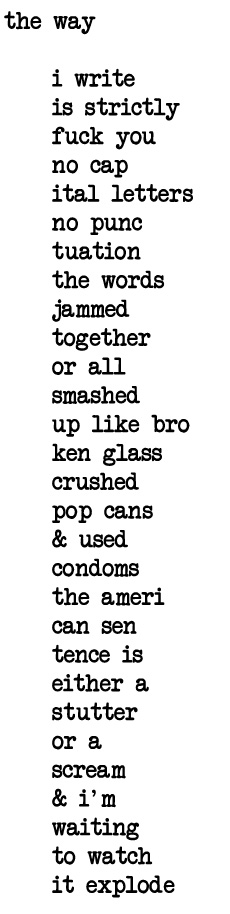

Writing

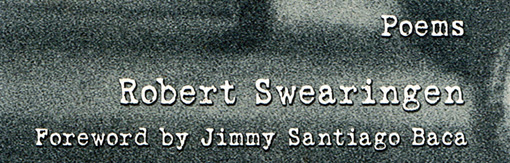

poetry is dangerous work. Dangerous because nobody pays you to do it. So, why try, right? Dangerous because it can tear off the top of your head and expose the deepest most secret part of your self to the universe. And, dangerous because it invites all your private demons to dance on your eyelids. I read STREET MILK when it first came out several years ago, thought about writing a review, but had no real place to publish it. Since then the book has haunted me in strange and peculiar ways. I’d known Robert Swearingen only because we had occasionally appeared at the same readings. But I didn’t know Swearingen’s work that well. I recall his reading Interview In Milwaukee which was a savagely comic take on a poet who is interviewed for a job by feminist but I didn’t know much else about the man. I didn’t know that he was from Hammond, Indiana, which is not that far from Chicago. I didn’t know that he had a degree in English. I didn’t know that his uncle had worked most of his life for the Illinois Central Railroad. My grandfather, my father, and my uncle had all worked for the Illinois Central back in the 1920s.

STREET MILK is one of those flawed, imperfect books that occasionally flame to life like a damaged roman candles. It is a book of brilliant sparks rather than huge explosions and maybe this is partly why I am attracted to it. The Hal Sirowitz blurb on the back cover of the book is really misleading. Sirowitz invokes the name of Charles Bukowski to make his point that this is a book about work and survival and while both of these themes are interwoven in many poems, STREET MILK is really a kind of journey through hell. Rimbaud is a name that could more easily be invoked. Or, Dante, though it would have to be a secular Dante, an addicted Dante, a Dante inflicted with nightmare visions and the horrors of the streets.

Robert Swearingen’s poetry is nothing like the poetry of Charles Bukowski. Swearingen’s poetry has a kind of shattered lyricism to it. Bukowski’s poetry comes at you like a thrown chair in a beer bar where the juke is going and a worn out hooker is trying to dodge the bottles in the air while she is putting her lipstick on. And, while Swearingen’s poetry is also about addiction, it really deals with the visions that addiction bring. Not the polish highball hangovers, the gut wrenching vomiting, and the howling hysterical landladies who are hounding Bukowski for the rent. Both Bukowski and Swearingen may have inhabited some of the same worlds including the bars but they are looking at the world with very different pairs of eyes.

And, this isn’t bad. What it means is that Swearingen isn’t trying to be at all like Bukowski. What it means is that Swearingen is attempting in this book to find, maybe to rescue something from his own broken world. Since I don’t know Robert Swearingen very well, I have no idea how long he has been writing poetry, how long he has been working on the manuscript that eventually became STREET MILK. The book was published in 2002. According to the brief bio on the back cover of the book, Swearingen was born in 1946, which means he was fifty six when STREET MILK appeared. By anyone’s standards, fifty six is late to be bringing out a first book of poetry. Late, but brave. It is often foolhardy to be publishing poetry at all, since so few people read it. But it is always brave because it is a wager made against the void. An intimate bet with the blood that what you wrote is worthy of being read and remembered. Even for a nano second.

I die of thirst beside the fountain

Next to the fire

I’m shaking tooth on tooth

This epigram which kicks the book off so aptly was written by Francois Villon. I can’t think of a more fitting way to begin STREET MILK. Villon, who was both outlaw and teacher, could just as easily have been Swearingen’s brother. In fact, he is the spiritual brother to anyone who writes from the street, the bar, the skidrow hotel, and even the jail. Villon continues to provide the archetype for the poet who writes from under the floorboards of any culture.

When Villon writes, I’m shaking tooth on tooth, he’s speaking for all of us. Especially, Robert Swearingen. Villon is talking about a kind of primal shaking when you encounter life at its rawest. And, Swearingen’s best poems capture the visceral feel of that shaking.

STREET MILK could easily have been an autobiographical novel. The first section focuses on Swearingen’s childhood, his railroad man uncle, his grandmother who locked him away in the basement, and Swearingen working at Bethlehem Steel. The best poems in this section are Hero Worship, Uncle Archie’s Basement, Gary Indiana, Bethlehem Steel, 265 Days Without An Accident. The best thing about these poems is that they were rooted in a gritty midwest reality that I knew. I wanted to know more about Swearingen’s father, the grandmother and why she locked him away, Uncle Archie who liked his whiskey, and Jimmy the friend who went missing. Maybe Swearingen will write more about these people in a future book of poetry. I hope he does because I care about them. I care about their shortcomings, their brokenness, their passions, and their deadendedness. They are really what good poetry is all about. They are the kinds of stories that make us all dream.

The second section of STREET MILK is a quantum leap from the reality of the railroad yards, grandma’s house, and the steel mill to the floating surreality of alcoholic visions. Three Day Drunks Usually End Ugly, the poem that opens this section, is the kind of hallucination that you don’t easily forget. And, while this poem could have been a little more tightly edited, it still works powerfully on the imagination. When Swearingen writes, Someone is looking out through the bones of my face, you know he is taking you to a whole new level of the visionary experience. This certainly isn’t where Bukowski wrote from. In fact, it comes closer to A SEASON IN HELL or maybe NAKED LUNCH. Swearingen follows this line with the following lines.

I’m riding the bus with these corpses the driver is

bleeding from his feet and all I have to read is LES

MISERABLES…

Not all of the poems of the second section are as good as Three Day Drunk, but several come very close. I really liked The Funeral, Street Milk, Insomnia Redux, Gunshots From Lovers, Shopping On Acid, and Insomnia. In fact, I think Gunshots might be that one perfect poem that Swearingen has written so far. It teeters right on the edge of oblivion. The last couple of lines are just plain gorgeous in their suicidal simplicity.

while we collected our sonnets of glass

and hid the guns

from our mouths.

Have you ever come across maybe two or three lines of poetry you wish you had written? These are the three lines in this book that I have fallen in love with. STREET MILK is what I would call a beautifully damaged work of art. Damaged and powerful. The laughter in Interview In Milwaukee and Shopping On Acid approaches a kind of down and out slapstick. These poems are, by turns, hilarious and horrible and at the same time you know that what you are laughing at is a glimpse of the void.

STREET MILK

is destined for cult book status. Todd Moore | October 27, 2008

Please click the image to see the back cover.

Street Milk Author: Robert Swearingen – ISBN: 0971534403 : 9780971534407 – Format: Paperback Size: 140x215mm – Pages: 75 – Weight: .15 Kg. – Published: AtlasBooks (Central Avenue Press) – December 2007 – List Price: 10 EURO – Availability: In Print – Subjects: Poetry & poets

In this collection of 44 poems, Robert Swearingen takes the reader on a journey through a life that is by turns raw, humorous, and at times, poignant. With a brutal honesty that asks for neither pity nor condemnation, he speaks in the context of personal experience, of a life of material success, selfishness, loss, folly, loneliness, and the hope for a redemption that will transcend the mistakes of the past.

Robert Swearingen’s book Street Milk is available directly here on this page and soon via our THE SHOP page where you will find also Todd Moore books by clicking here…

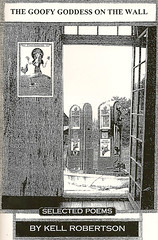

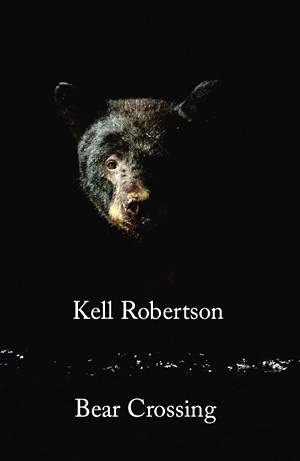

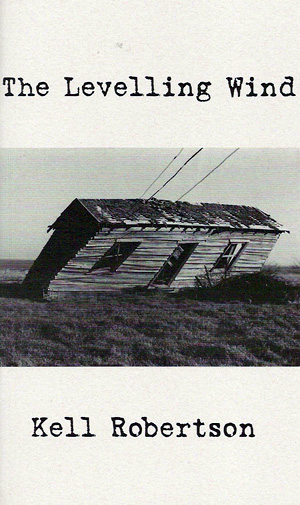

In some ways, Kell Robertson could have been a character in a Cormac McCarthy novel. He is part of John Grady Cole’s world or Billy Parham’s world. While Robertson is not a Cowboy Poet, he is a poet from a nearly vanished time. Born in 1930 in rural Kansas, he was on the road by the mid forties and certainly had seen a good deal of the west by 1950, the same time period that the major characters of THE CROSSING TRILOGY lived through. The fact that Robertson was living in the west and southwest in the forties and fifties goes a long way in giving his voice and vision the kind of authenticity that is lacking in most so called Cowboy Poets. Robertson’s best poems have a sound in them that you find in the very best moments of a Max Evans’ novel, a Cormac McCarthy novel, and especially in William Faulkner’s short novel THE BEAR. Robertson heard the best of all talking and somehow he was able to get that voice, the sound of that voice, the bourbon gravelly shorthand drawl of that voice into poems that I can only call masterpieces. Not every Kell Robertson poem is a masterpiece. But poems such as Bear Crossing, Almost Suicide, For My Stepfather, A Horse Called Desperation, Pretty Boy Floyd, and The Gunfighter are almost certainly the best of all talking.

In some ways, Kell Robertson could have been a character in a Cormac McCarthy novel. He is part of John Grady Cole’s world or Billy Parham’s world. While Robertson is not a Cowboy Poet, he is a poet from a nearly vanished time. Born in 1930 in rural Kansas, he was on the road by the mid forties and certainly had seen a good deal of the west by 1950, the same time period that the major characters of THE CROSSING TRILOGY lived through. The fact that Robertson was living in the west and southwest in the forties and fifties goes a long way in giving his voice and vision the kind of authenticity that is lacking in most so called Cowboy Poets. Robertson’s best poems have a sound in them that you find in the very best moments of a Max Evans’ novel, a Cormac McCarthy novel, and especially in William Faulkner’s short novel THE BEAR. Robertson heard the best of all talking and somehow he was able to get that voice, the sound of that voice, the bourbon gravelly shorthand drawl of that voice into poems that I can only call masterpieces. Not every Kell Robertson poem is a masterpiece. But poems such as Bear Crossing, Almost Suicide, For My Stepfather, A Horse Called Desperation, Pretty Boy Floyd, and The Gunfighter are almost certainly the best of all talking. The fascinating thing about Kell Robertson’s poetry is that it could just as easily have been written beginning in 1920 as it was beginning in the 1960s. Robertson’s poetry never really depended on T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, or Robert Frost. In some ways it depends more on the stories of Ernest Hemingway and the song lyrics of Hank Williams. The core of the best of Kell Robertson’s work depends partly on the leanest of american sentences. It’s very possible Bukowski figures in there somewhere except that Bukowski’s poetry is heavily urban and situated right at the street level while Robertson’s poetry is heavily western and rural, situated somewhere between a cantina, a mesa, and a bus station. Bukowski’s poetry is a celebration of the visceral. Robertson’s poetry has always been a viscerally raw western lament, a kind of death song in the best tradition of Sam Peckinpah. Every death song should have some blood in it.

The fascinating thing about Kell Robertson’s poetry is that it could just as easily have been written beginning in 1920 as it was beginning in the 1960s. Robertson’s poetry never really depended on T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, or Robert Frost. In some ways it depends more on the stories of Ernest Hemingway and the song lyrics of Hank Williams. The core of the best of Kell Robertson’s work depends partly on the leanest of american sentences. It’s very possible Bukowski figures in there somewhere except that Bukowski’s poetry is heavily urban and situated right at the street level while Robertson’s poetry is heavily western and rural, situated somewhere between a cantina, a mesa, and a bus station. Bukowski’s poetry is a celebration of the visceral. Robertson’s poetry has always been a viscerally raw western lament, a kind of death song in the best tradition of Sam Peckinpah. Every death song should have some blood in it.

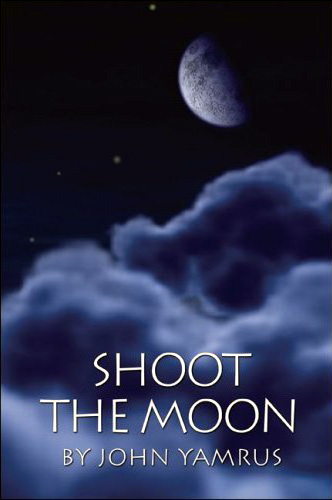

One influence that John Yamrus has not mentioned is Gerald Locklin. As I stated before, I have read through both books carefully and can’t find a mention of his name anywhere except in a blurb on the back cover of One Step At A Time. The fact is, I find as much Gerald Locklin in these poems as I do Charles Bukowski. Equal parts to be exact. But, I do not mean these remarks as a diminishment of John Yamrus’ poetry. In fact, what I am suggesting is that Yamrus, maybe from early on, had somehow found a way to synthesize the styles of Charles Bukowski and Gerald Locklin. This is no mean feat when you stop to think about it. Bukowski met life headon and with no reservations. He was the rowdy, the tough guy, the down and outer slouched over a drink at a bar. Locklin, on the other hand, continues to write a kind of dialed down poem, full of failed attempts and attempted failures, a man who loves jazz and books, a poet who prefers meditation to action, a poet who lives the nondramatic life and who writes from a stance of self effacement.

One influence that John Yamrus has not mentioned is Gerald Locklin. As I stated before, I have read through both books carefully and can’t find a mention of his name anywhere except in a blurb on the back cover of One Step At A Time. The fact is, I find as much Gerald Locklin in these poems as I do Charles Bukowski. Equal parts to be exact. But, I do not mean these remarks as a diminishment of John Yamrus’ poetry. In fact, what I am suggesting is that Yamrus, maybe from early on, had somehow found a way to synthesize the styles of Charles Bukowski and Gerald Locklin. This is no mean feat when you stop to think about it. Bukowski met life headon and with no reservations. He was the rowdy, the tough guy, the down and outer slouched over a drink at a bar. Locklin, on the other hand, continues to write a kind of dialed down poem, full of failed attempts and attempted failures, a man who loves jazz and books, a poet who prefers meditation to action, a poet who lives the nondramatic life and who writes from a stance of self effacement. John Yamrus

John Yamrus

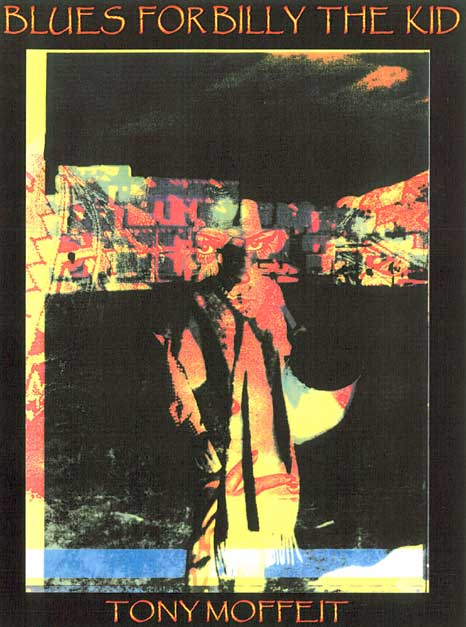

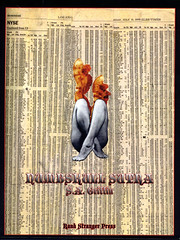

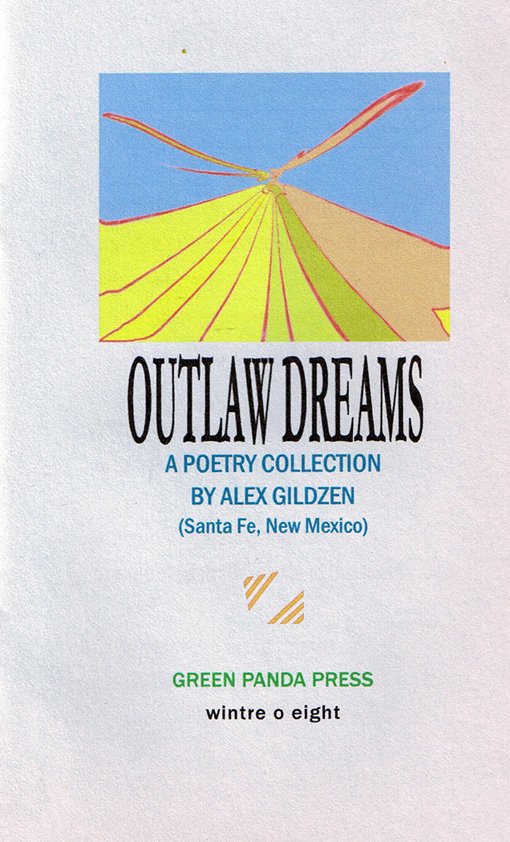

One thing to keep in mind is that no Outlaw Poet is like any other. Every Outlaw Poet is different from every other one both in life style and the way that he stands against the culture. Allen Ginsberg and Jack Micheline were both Outlaws but they were both as unalike as any two people could have been, both in their work and in their life styles. The same goes for Tony Moffeit and Kell Robertson. If anything Tony is a kind of blues/shaman poet while Kell is the original half horse half alligator american wild man poet. The same goes for S. A. Griffin and Alex Gildzen. Both poets are the pure products of the Dream Factory Myth. But, they mine that myth so differently. And, they both know that inside the flicker of that movie light there is a powerful darkness that most of us have only just begun to tap into.

One thing to keep in mind is that no Outlaw Poet is like any other. Every Outlaw Poet is different from every other one both in life style and the way that he stands against the culture. Allen Ginsberg and Jack Micheline were both Outlaws but they were both as unalike as any two people could have been, both in their work and in their life styles. The same goes for Tony Moffeit and Kell Robertson. If anything Tony is a kind of blues/shaman poet while Kell is the original half horse half alligator american wild man poet. The same goes for S. A. Griffin and Alex Gildzen. Both poets are the pure products of the Dream Factory Myth. But, they mine that myth so differently. And, they both know that inside the flicker of that movie light there is a powerful darkness that most of us have only just begun to tap into.

After that event, Gildzen decided to make a career change and was hired by then-Curator Dean Keller to assist him in the univeristy library’s Special Collections Department in 1971. During his tenure in Special Collections, Gildzen acquired the archives of the Open Theater, as well as the papers of its director Joseph Chaikin and major playwright Jean-Claude van Itallie. He also acquired the papers of Group Theater member Robert Lewis, film historians Gerald Mast and James Robert Parish, and silent screen star Lois Wilson. He retired as Curator in 1993 after thirty years of service at Kent State.

After that event, Gildzen decided to make a career change and was hired by then-Curator Dean Keller to assist him in the univeristy library’s Special Collections Department in 1971. During his tenure in Special Collections, Gildzen acquired the archives of the Open Theater, as well as the papers of its director Joseph Chaikin and major playwright Jean-Claude van Itallie. He also acquired the papers of Group Theater member Robert Lewis, film historians Gerald Mast and James Robert Parish, and silent screen star Lois Wilson. He retired as Curator in 1993 after thirty years of service at Kent State.

TONY MOFFEIT | AMERICAN BLUES OUTLAW POETRY ANARCHIC DREAM

TONY MOFFEIT | AMERICAN BLUES OUTLAW POETRY ANARCHIC DREAM